What does it take for a jewelry artifact, whether it be a single stone or a hoard of gold, to be declared “cursed”? Well, it seems the main ingredient is a populace with a very active imagination, and successive owners who are willing to carry on the legend even if they’ve escaped with all their limbs. Here is a great piece by JR Thorpe from Bustle about the 5 Strangest Jewelry Curse Stories.

Like all fantastically expensive objects, jewelry of the most high-end kind tends to attract theft, disagreement, political problems, and other intrigue; but that’s just a fact of its desirability. Beyond that, historically, jewelry curses are often invented aspects to give a potential buyer a little bit more flavor. (The La Peregrina Pearl owned by Elizabeth Taylor has been blamed for the fact that she married eight times, but it’s more realistic to blame that on her interpersonal skills than on a blameless bit of cultivated oyster.)

The actual origin of many jewels without proper provenance is frankly difficult to ascertain, beyond geographic region. And it’s mildly astonishing that so many of the “cursed” variety appear to have a variant on the same origin story: beginning life as the eye of an idol in some remote country in the British Empire (usually India), stolen in a way that attracted the vengeance of the gods, passed on to a succession of owners who all met bizarre bad luck. The fact that this story popped up regularly in Victorian literature (Wilkie Collins’ The Moonstone, for instance, and a Sherlock Holmes story by Arthur Conan Doyle) attests that it was part of the popular fiction of the time, and potential sellers likely thought a bit of bloody intrigue would raise the value. This is the interesting thing about jewels: unlike basically any other object (like, say, a washing machine), a potentially murderous history is an asset to buyers, not a turn-off.

Here are five of the strangest cursed pieces of jewelry in history, from the diamond that only Queens can wear for fear of a fiery death to the golden hoard that nearly caused the end of a museum.

The Delhi Purple Sapphire

Few of the curses on this list can be traced to one person in particular, but in the case of the Delhi Purple Sapphire, which is actually an amethyst, we can make a pretty accurate guess: it was most likely invented by Edward Heron-Allen, a fanciful Victorian gentleman with a tendency towards the occult and fantastic.

Few of the curses on this list can be traced to one person in particular, but in the case of the Delhi Purple Sapphire, which is actually an amethyst, we can make a pretty accurate guess: it was most likely invented by Edward Heron-Allen, a fanciful Victorian gentleman with a tendency towards the occult and fantastic.

The amethyst’s “cursed” origins come mostly from the letter sent with it to the Natural History Museum in London after his death by his daughter, in which all kinds of outrageous claims are made. On one occasion, apparently, Heron-Allen tried to give it away to an opera singer friend, who then gave it back after she mysteriously lost her voice forever. Henry was reportedly sufficiently rattled that he kept the jewel in his bank inside seven safe-deposit boxes, because he clearly knew how to make a dramatic flourish. The daughter’s letter ended with a plea for the museum to “throw it in the sea,” but thus far, the amethyst appears to have been managed without a great deal of difficulty. Funny, that.

The Hope Diamond

Reality and truth when it comes to the Hope Diamond are fantastically mixed up. We actually know little of its origins except that it was bought around 1668 in India by a man named Jean-Baptiste Tavernier. (Myth dictates he was torn apart by wild dogs for the purchase, but he wasn't.) Its legend after that appears to be largely the fabrication of an over-excited press, though it does appear as if the wealthy McLean family (matriarch Evalyn is pictured) who purchased it from Cartier in the early 20th century did have what looks like bad luck: sanitariums, suicides, alcoholism, and other domestic tragedies abounded for them. (These days, we’d declare the cause a highly toxic family and send them all to therapy.) The source of its long list of so-called cursed ex-owners, however, seems to be the creation of a New York newspaper, and little, if any, of it can be substantiated. It belongs to the Smithsonian these days, in case you want to go check it out.

Reality and truth when it comes to the Hope Diamond are fantastically mixed up. We actually know little of its origins except that it was bought around 1668 in India by a man named Jean-Baptiste Tavernier. (Myth dictates he was torn apart by wild dogs for the purchase, but he wasn't.) Its legend after that appears to be largely the fabrication of an over-excited press, though it does appear as if the wealthy McLean family (matriarch Evalyn is pictured) who purchased it from Cartier in the early 20th century did have what looks like bad luck: sanitariums, suicides, alcoholism, and other domestic tragedies abounded for them. (These days, we’d declare the cause a highly toxic family and send them all to therapy.) The source of its long list of so-called cursed ex-owners, however, seems to be the creation of a New York newspaper, and little, if any, of it can be substantiated. It belongs to the Smithsonian these days, in case you want to go check it out.

The Lydian Hoard

Curses can be bureaucratic as well as dramatic. You can guarantee that the Metropolitan Museum of Art regards the Lydian Hoard as a cursed treasure and is very glad to be rid of it, but that’s due to a scandal of its own making.

Curses can be bureaucratic as well as dramatic. You can guarantee that the Metropolitan Museum of Art regards the Lydian Hoard as a cursed treasure and is very glad to be rid of it, but that’s due to a scandal of its own making.

The Met obtained the pieces, which were part of an ancient Turkey burial mound, in the 1960s for around $1.5 million, and proceeded to hide them in storage; they weren’t even recorded in the catalogue of the museum’s possessions. The secrecy was down to the fact that they likely knew the Hoard’s origins weren’t perhaps strictly legal. They were right; the gold had been stolen by villagers near the mound in 1966 and handed onto smugglers. It took years of digging by dedicated journalists before the Met would admit that the Hoard existed and that it did indeed originate in Turkey. Turkey, incensed, mounted a court case, insisting that the Met hand them back. The case humiliated the museum and forced them to return the Hoard with a public admission of their own guilt.

Priam’s Treasure

The 19th century German archaeologist Heinrich Schliemann was an unusual man, by all accounts, particularly because his crazy claim to have discovered the ancient city of Troy turned out, bizarrely, to be true. He and his wife Sophie found a spectacular array of golden jewelry in the ruins of the city, in which Sophie was infamously pictured; but, like the Lydian Hoard, the ancient neck piece and headgear (termed Priam’s Hoard, after the king of Troy from Homer’s Aeneid) attracted its fair share of trouble. Schliemann took the pieces back to Germany, but during World War II’s Russian takeover of Berlin they “disappeared”. Russia claimed not to have the faintest idea where they were for decades, but eventually admitted to having them in one of its museums, and is currently absolutely refusing to give them back, saying that they’re a kind of recompense for German destruction of Russian cities.

The 19th century German archaeologist Heinrich Schliemann was an unusual man, by all accounts, particularly because his crazy claim to have discovered the ancient city of Troy turned out, bizarrely, to be true. He and his wife Sophie found a spectacular array of golden jewelry in the ruins of the city, in which Sophie was infamously pictured; but, like the Lydian Hoard, the ancient neck piece and headgear (termed Priam’s Hoard, after the king of Troy from Homer’s Aeneid) attracted its fair share of trouble. Schliemann took the pieces back to Germany, but during World War II’s Russian takeover of Berlin they “disappeared”. Russia claimed not to have the faintest idea where they were for decades, but eventually admitted to having them in one of its museums, and is currently absolutely refusing to give them back, saying that they’re a kind of recompense for German destruction of Russian cities.

For its part, one of Berlin's museums has a spectacularly passive-aggressive display of copies of the Treasure, with a very pointed caption about waiting for the Russians to give them back. In case you were wondering, ancient Troy is in modern Turkey, and their government appears not to have been given a word in edgeways.

The Koh-i-Noor Diamond

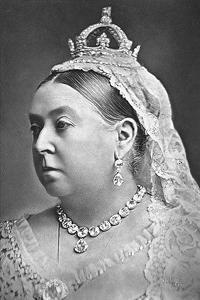

The interesting thing about the Koh-i-Noor diamond (the name means "mountain of light" in Persian) isn’t that it’s at the center of a continued diplomatic spat (though it is; the Indian government only recently abandoned its latest attempt to get it back from the English Crown). It’s that its use continues to be governed by its legends.

The interesting thing about the Koh-i-Noor diamond (the name means "mountain of light" in Persian) isn’t that it’s at the center of a continued diplomatic spat (though it is; the Indian government only recently abandoned its latest attempt to get it back from the English Crown). It’s that its use continues to be governed by its legends.

The Koh-i-Noor Diamond originates from India, though it made its way into English hands after its owners, as kings are inclined to do, kept being overthrown or assassinated. It is reported to be allowed to be worn only “by God or woman;” any man who attempted to use it as adornment would, presumably, suffer and die. As part of the Queen’s Crown Jewels, it’s only ever been worn by British female royals, including the Queen Mother, and will likely continue to be so. The English might be very practical people, but they never met a superstition they didn’t like.

Images: Royal Collection, Library Of Congress, Dillum, Arif Solak/Wikimedia Commons

This article first appeared on Bustle from author JR Thorpe in Lifestyle