Diamond News Archives

- Category: News Archives

- Hits: 683

Media playback is unsupported on your device

Two metal detectorists stole a £3m Viking hoard that experts say has the potential to "rewrite history".

George Powell and Layton Davies dug up about 300 coins in a field in Eye, near Leominster, Herefordshire, in 2015.

They did not declare the 1,100-year-old find, said to be one of the biggest to date, and instead sold it to dealers.

They were convicted of theft and concealing their find. Coin sellers Simon Wicks and Paul Wells were also convicted on the concealment charge.

The hoard included a 9th Century gold ring, a dragon's head bracelet, a silver ingot and a crystal rock pendant. Just 31 coins - worth between £10,000 and £50,000 - and some pieces of jewellery have been recovered, but the majority is still missing.

"They must be concealed in one or more places or by now having been concealed have been dispersed never to be reassembled as a hoard of such coinage again," prosecutor, Kevin Hegarty QC, said.

During their trial at Worcester Crown Court, Powell, 38, of Newport, and Davies, 51, of Pontypridd, had denied deliberately ignoring the Treasure Act, which demands significant finds be declared.

Experts say the coins, which are Saxon and believed to have been hidden by a Viking, provide fresh information about the unification of England and show there was an alliance previously not thought to exist between the kings of Mercia and Wessex.

"These coins enable us to re-interpret our history at a key moment...

- Category: News Archives

- Hits: 697

Traders working on the floor of the New York Stock Exchange.

Drew Angerer | Getty Images

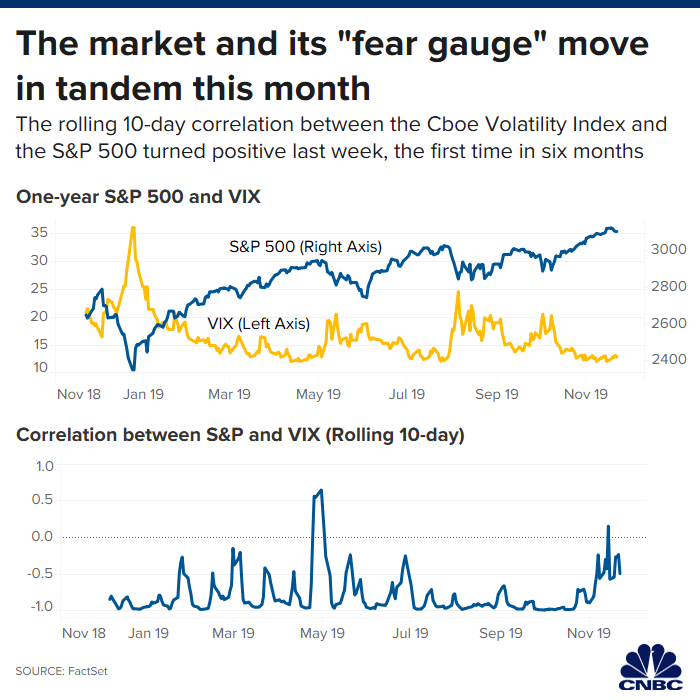

An unusual trend in the stock market emerged recently as the latest sign that perhaps greed is the driving force behind the rally and investors are ignoring some key risks.

Wall Street's "fear gauge" the Cboe Volatility Index[1], which typically trades inversely with stock prices, started moving in tandem at times with the S&P 500[2] earlier this month. The rolling 10-day correlation between the VIX and the S&P 500 turned positive on Nov. 14, the first time this has happened in six months, according to FactSet.

"When this correlation, and like many others recently, get out of whack would imply that something else is driving stock prices," Roberto Friedlander, head of energy trading at Seaport Global, said in a note on Thursday.

The so-called VIX is a measure of the stock market's 30-day expected volatility computed from the market prices of the call and put options on the S&P 500. When the market goes down, investors would want to purchase insurance, which drives up the prices of put options and increases the VIX. The VIX decreases when there's less demand for put options as the market rises. That's why it tends to move inversely to equities.

The fear gauge is also flirting with a two-year low, hovering around just 13 points, as investors cheer the record-setting rally, shrugging off a never-ending trade war and a heated impeachment probe into President Donald Trump.

The S&P 500's strong performance this quarter has pushed its gains this year to nearly 25%, on pace for its biggest annual gain since 2013. While many...

- Category: News Archives

- Hits: 761

Gluskin Sheff's David Rosenberg expects negative growth to hit the U.S. economy sooner than Wall Street anticipates.

When his scenario officially unfolds, the long-time market skeptic warns, it will likely hit consumers first.

"Has the recession started officially? No, it hasn't. But the recessionary pressures are building," the firm's chief economist and strategist told CNBC's "Trading Nation[1]" on Thursday. "It's all basically just about lags and effects. And, I think that the consumer is next in line, and we're going to see more evidence of that in the first half of 2020."

Rosenberg warned on "Trading Nation" in January that a recession was virtually unavoidable this year[2]. Two months ago, he pushed his recessionary timeline out to less than 12 months away.

"We're at almost 0% [GDP] growth[3]," he said. "My bean count for Q4 has a minus sign in front of it."

Former Federal Reserve Chair Janet Yellen is also expressing concern about the economy.

During Thursday's World Business Forum, Yellen said there's "good reason to worry"[4] about the U.S. economy sliding into a recession. But unlike Rosenberg, she believes it's in "excellent" shape right now.

Rosenberg makes the case that the economy is not done feeling the effects of the Federal Reserve's decision to raise interest rates in 2018. He believes the Fed's action to begin lowering rates this year is not mitigating the impact.

"It's a classic game of dominoes. It's never always the same. But you have to know your history, and especially after a policy-tightening cycle, which we had from the Fed," he said. "You don't shock a part of the economy without shocking other parts with a lag."

He also...

- Category: News Archives

- Hits: 1042

Last week in Zurich, Richard Clarida, vice chairman of the US Federal Reserve bank, made a speech[1] about how monetary policy—the raising and lowering of interest rates—has become more challenging in a low inflation environment. Among the figures and evidence he presented was startling picture of what central bankers call r*.

r* is a calculation of the natural rate of interest, or roughly the short term or risk-free interest rate that would prevail if monetary policy was neutral (not trying to boost or slow the economy). It fell after the financial crisis and stayed low and is beginning to look like what economists call a structural change. Asset prices tend to move around, but sometimes they change permanently, or their natural level changes for a very long time. That r* has stayed so low for more than 10 years suggests a big change.

Federal Reserve

Although r* doesn’t represent a bond that is directly traded, it is one of the most important interest rates in the economy. First it tells us (and central bankers) if monetary policy is expansionary or not: If they set rates above or below r* they are contracting or juicing the economy. But r* is also the foundation of the bond market. Bond yields are a function of r*, expected inflation, and a premium to compensate investors for bearing the risks involved with holding bonds for longer. A structurally lower r* means lower interest rates on all bonds, and this can have profound implications for the economy.

Why did it change?

The trend is global so whatever changed, it happened to all industrial countries. Economists cite several factors[2] (pdf)...

- Category: News Archives

- Hits: 968

When the US and ultimately the rest of the Western world began to engage China, resulting in China finally being allowed into the World Trade Organization in the early 2000s, no one really expected the outcomes we see today.

There is no simple disengagement path, given the scope of economic and legal entanglements. This isn’t a “trade” we can simply walk away from.

But it is also one that, if allowed to continue in its current form, could lead to a loss of personal freedom for Western civilization. It really is that much of an existential question.

Doing nothing isn’t an especially good option because, like it or not, the world is becoming something quite different than we expected just a few years ago—not just technologically, but geopolitically and socially.

China and the West

Let’s begin with how we got here.

My generation came of age during the Cold War. China was a huge, impoverished odd duck in those years. In the late 1970s, China began slowly opening to the West. Change unfolded gradually but by the 1990s, serious people wanted to bring China into the modern world, and China wanted to join it.

Understand that China’s total GDP in 1980 was under $90 billion in current dollars. Today, it is over $12 trillion. The world has never seen such enormous economic growth[1] in such a short time.

Meanwhile, the Soviet Union collapsed and the internet was born. The US, as sole superpower, saw opportunities everywhere. American businesses shifted production to lower-cost countries. Thus came the incredible extension of globalization.

We in the Western world thought (somewhat arrogantly, in hindsight) everyone else wanted to be like us. It made sense....